We’ve all seen the lists of books that “you must read before you die” or that “you should have read in high school.” I’m personally not a believer in placing too many “shoulds” around our reading lives—my thinking is that you should read what you want to, and not feel any guilt about the books you read OR the ones you skip. That said, I pride myself on being well-read and like to have a basic understanding of a broad range of books, including the classics.

My 2017 Reading Challenge was all about acquainting myself with some of those older, established books. I checked twelve classics off my list, reading through one book from each decade of the last century, but that still left me with many classics I still want to read (but might need some prompting to actually pick up). Which lead’s to this month’s Challenge theme.

Shortly after Luke and I started dating, we had THE TALK. You know, the one all early couples have about what books each member has and hasn’t read. (All couples might not be accurate; maybe just all nerdy couples, a category in which Luke and I most definitely belong.) As we compared notes on the books we’d each read in high school, we were both surprised by the lack of overlap. I was appalled that he hadn’t read To Kill a Mockingbird, shocked that he’d never read the words of Mark Twain, and extremely jealous that he hadn’t had to suffer through Moby Dick. For Luke’s part, he couldn’t believe that I’d never had the privilege of studying Fahrenheit 451 or Frankenstein (a book we went on to read together on our honeymoon).

One of the books Luke insisted I one day needed to read was Of Mice and Men. I held out for many years, but this month I knew this book’s time had finally come.

I might be the only person in America who still hadn’t read this book, but in case there are others of you who have yet to be initiated into the OMAM club, here’s a little background. Published in 1937, the book (technically a novella) tells the story of George and Lennie, two displaced migrant workers who have nothing in the world except each other and their shared dream of one day becoming landowners. The men are opposites in every way: George is small, shrewd, and outgoing; Lennie is large, reserved, and not very bright. But they have stuck together through years of hardship and hard work, and their friendship sets them apart from the lonely men they’ve encountered in years of migrant work.

After fleeing their last job to escape false accusations that Lennie had raped a woman, the men find themselves on a farm in Salinas, California. They seem to be establishing some good connections, but soon Lennie’s combined strength and naïveté lead to disaster for both men.

My initial response when finishing this book was a strong desire to hurl it across the room—perhaps even at my husband himself, for recommending that I read it! I knew that it would be sad, but had no idea just how devastating the conclusion would be. (Warning: if you were thinking about reading this, but are a sensitive reader, SKIP IT!) I understand why it’s become a classic. Steinbeck’s sparse narration captures the stark plight of his characters and the harshness of farm life during the Depression. Lennie and George’s relationship is endearing, but it is a lone bright spot in a very depressing life. Which makes the book’s conclusion even more difficult to stomach! I appreciate books that capture the atrocity and brutality that exist in our world—but that doesn’t mean that I enjoy them.

With its obvious themes and abundant metaphors, Of Mice and Men is awash with opportunities for literary probing. I love doing this on my own but recognize my own inability to fully notice or comprehend every analogy and motif. This is why I loved my high school English classes. Many readers claim that studying a book in school ruins it for them, but I found the opposite to be true: the discussions we had and the papers I wrote about the books I read as a student almost always enhanced my enjoyment and appreciation for those novels. To compensate for the lack of discussion happening when I read classics as an adult, I often follow up the novel with a perusal of a few commentaries. (SparkNotes, of course, as well as whatever else I can find online.) I definitely benefitted from the enrichment of these supplementary sources after reading Of Mice and Men. In particular, they helped me understand the book’s ambiguous portrayal of women.

I have no doubt I would have appreciated this book more in my school years. And I can see why it had such a profound impact on Luke when he read it as a teen. Although it wasn’t a favorite for me, I have no regrets about having checked this classic off my list.

MY RATING: 3 stars.

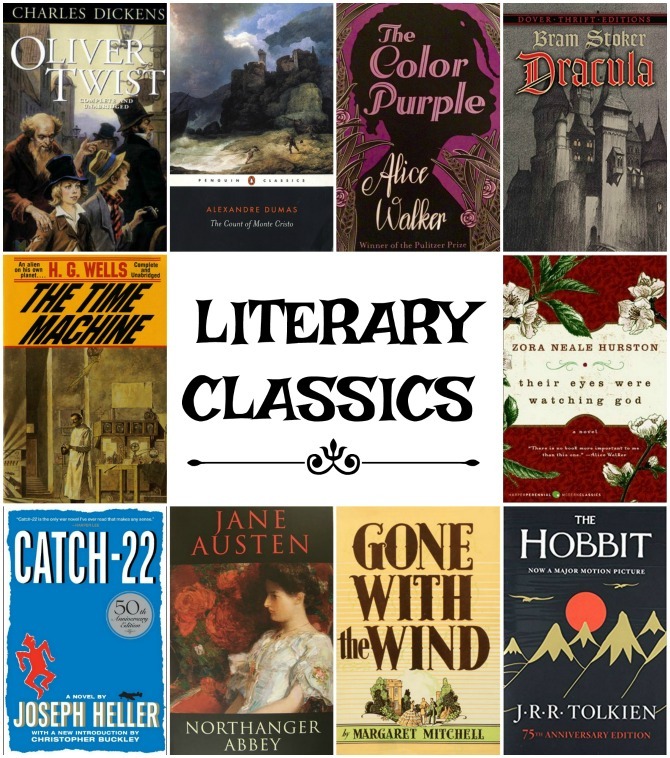

OTHER CLASSICS I’VE BEEN MEANING TO READ

Northanger Abbey, by Jane Austen (published in 1817)

Oliver Twist, by Charles Dickens (published in 1838)

The Count of Monte Cristo, by Alexandre Dumas (published in 1884)

The Time Machine, by H. G. Wells (published in 1895)

Dracula, by Bram Stoker (published in 1897)

Gone With the Wind, by Margaret Mitchell (published in 1936)

Their Eyes Were Watching God, by Zora Neale Hurston (published in 1937)

The Hobbit, by J.R.R. Tolkien (published in 1937)

Catch-22, by Joseph Heller (published in 1961)

The Color Purple, by Alice Walker (published in 1982)

Have you read Of Mice and Men? What did you think?

What is your favorite classic novel? What is one classic you’ve been meaning to read?