If you’ve been following along with my 2017 Reading Challenge, you’ll notice that we’ve approached the year’s halfway point. We (well, I) read through the Victorian era, the turn of the century, the first World War, the Roaring 20s, and the Great Depression, and now we’ve arrived in the 1940s.

The defining event of the decade was, of course, the Second World War, which dominated all aspects of life, including literature. The outbreak of war in 1939 brought an era of creative exuberance to a halt, as individuals were dispersed and attention was diverted to the war efforts. The rationing of paper affected the production of magazines and books, leading many to favor shorter forms such as short stories and poems. No important new authors appeared, and the most prominent literary efforts about the war were written by established authors.

In the years following the war, literature was dominated by a renewed attachment to religion. Another trend was the heavy use of allegory and symbolism to make powerful political points. Shorter novels also became more common. Novels tended to have a bleak tone and often focused on the darker side of humanity. Notable exceptions included books written for younger audiences, which rarely acknowledged the war or its aftermath.

My selection for a book written during the 1940s falls into that last category—one that does not acknowledge World War II (and actually takes place before its onset). I had been settled on reading I Capture the Castle for this category since before I even started the challenge; I’ve heard many readers cite this classic as a favorite, and my historical-based reading challenge was the nudge I needed to finally pick it up for myself. The book’s author, Dodie Smith, is best known for writing The Hundred and One Dalmatians. Smith was born in England in 1896, but she and her husband relocated to the United States in the 1940s to avoid legal difficulties associated with his being a conscientious objector during the war. Smith’s homesickeness for her home country inspired I Capture the Castle, and her longings for both home and a happier time are palpable throughout the book.

Set in the English countryside during the spring and summer of 1934, I Capture the Castle is a coming-of-age story told through the journals of 17-year-old Cassandra Mortmain. Cassandra and her eccentric family live in the English countryside where they are ten years into a 40-year lease on the dilapidated castle they call home. Cassandra’s father is a formerly successful author who has suffered from writer’s block since the release of his one-hit-wonder, written more than a decade ago. Mortmain is a widower and his very young second wife, Topaz, is an artist’s model and a bohemian spirit with a penchant for dancing (sans clothing) on the surrounding moors. The other members of the household include Cassandra’s beautiful older sister, Rose, who pines for a wealthy husband; their younger brother, Thomas; and Steven, the late maid’s handsome and loyal son who is in love with Cassandra.

At the novel’s opening, the Mortmain family is penniless, unable to pay the rent on their castle and selling off their furniture to simply put food on the table. With no prospects for improvement of their circumstances, their future looks bleak until the Cottons, a wealthy American family, inherit nearby Scoatney Hall and become the Mortmains’ landlords. Cassandra and Rose are intrigued by their (unmarried and handsome) new neighbors—Simon, the scholarly elder bother, who grew up in New England with their mother, and Neil, the fun-loving younger brother who was raised by the brothers’ British father in California. Rose is immediately drawn to Neil (the family heir) and she and Cassandra begin plotting ways to establish a love match that could rescue the Mortmains from destitution. Their plans seem to be succeeding, but a complicated web of love triangles begins to unfold that could compromise not only the family’s financial situation, but also Cassandra’s happiness.

Reading back over that plot summary, it occurs to me that at its surface, the book sounds fairly depressing. This couldn’t be further from the case. As its title would indicate, I Capture the Castle has a whimsical quality that permeates the writing style, the dialogue, the atmosphere, and even the story itself. I adored Cassandra’s self-aware and of-the-moment narration, which captures her surroundings and complicated emotions in a way only an adolescent narrator could. I resonated with her reflections on writing, particularly her (often futile) attempts to perfectly document every word, feeling, and circumstance as it is happening—so reminiscent of my own journaling. I enjoyed seeing Cassandra explore her relationship to faith and God, her attempts to understand the complicated individuals in her life, and her growing awareness of deeper truths about life, love, and even literature.

The Mortmain family is too comical to be believed, but Smith’s ability to capture Cassandra’s young voice is so realistic that at points in the book, I had to remind myself that I was reading a novel and not a memoir. I have to wonder at how much of Smith’s own story (or at least her emotions) factored into the writing. One obvious author-related element is the amount of page time dedicated to Cassandra’s reflections on the differences between her British upbringing and that of her new American friends. Many of my favorite books are by British authors, but the differences between British and American lifestyles is rarely laid out so succinctly. This aspect of the book made a lot of sense when I learned the author was a Brit living in America at the time of the book’s writing, and therefore had a personal connection to both cultures.

I’ve read a number of books lately in which the final paragraph (or sometimes a clever Afterword) simply made the novel, landing the story in an unexpected and brilliant way that either solidified my positive feelings toward the book or even transformed a hitherto negative impression into a positive one. Sadly, I Capture the Castle does not have such an ending. I don’t want to give too much away, but I will say that though I adored the novel, I found the conclusion disappointing. Artistically, it’s perfect, but it isn’t quite the fairytale ending I had hoped for. But lackluster conclusion notwithstanding, this is a wonderful novel that I am so glad to have read and will likely return to in the future.

My Rating: 4.5 stars

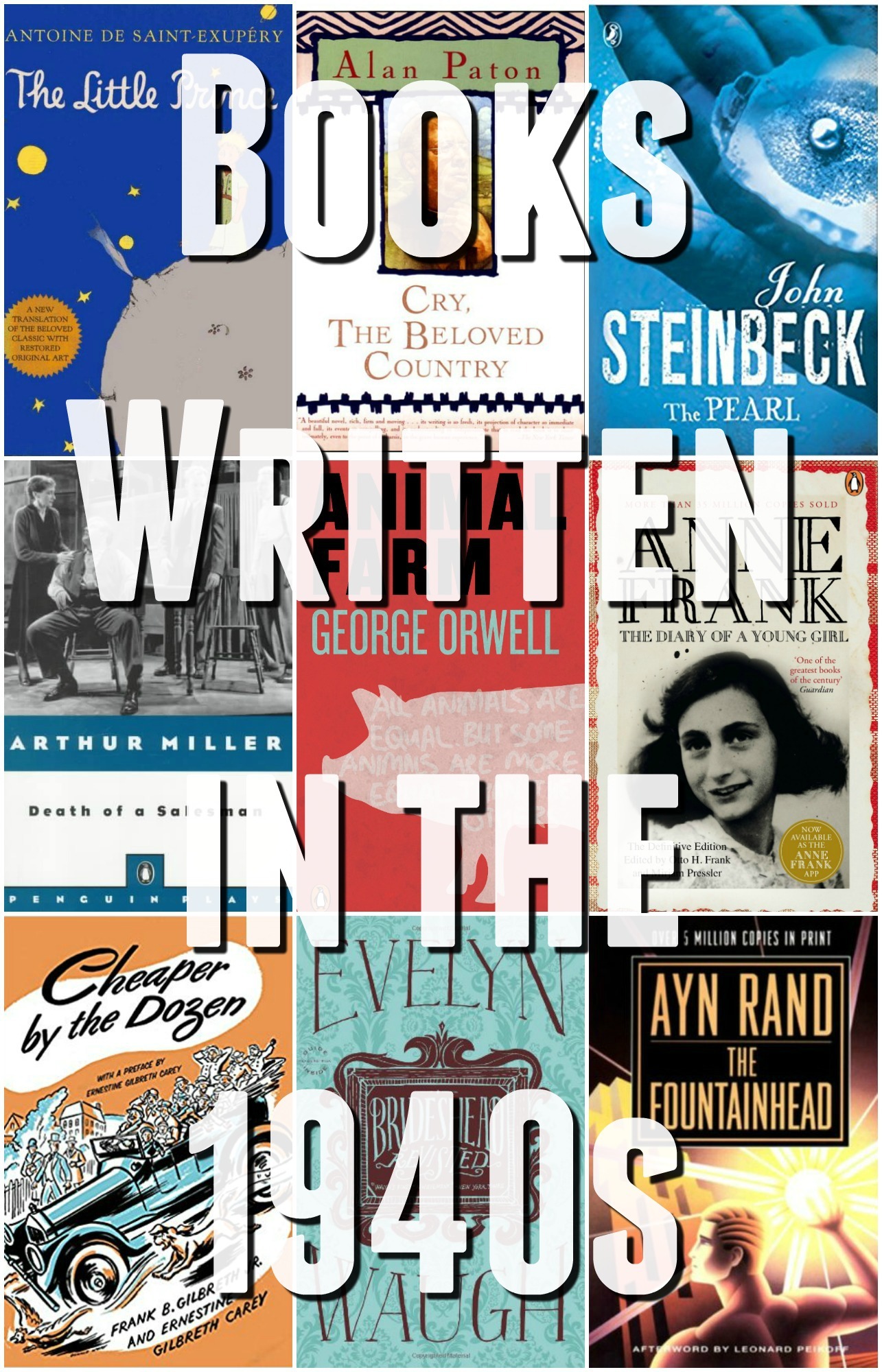

Other Books Written in the 1940s:

In looking at lists of the most popular books written during this decade, I was surprised by how few of the tiles I’d read. Of those I have read, not many are favorites. A few exceptions are The Diary of a Young Girl, which had a powerful affect on me when I read it as a preteen, and Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, a book I read for the first time last year. Another new-to-me favorite written during this decade is C.S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity, though it’s such a timeless book that it’s hard to think of it having been written in such a different era.

The Fountainhead, by Ayn Rand (published in 1943)

The Little Prince, by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry (published in 1943)

Animal Farm, by George Orwell (published in 1945)

Brideshead Revisited, by Evelyn Waugh (published in 1945)

The Diary of a Young Girl, by Anne Frank (published in 1947)

The Pearl, by John Steinbeck (published in 1947)

Cheaper by the Dozen, by Frank Bunker Gilbreth Jr. and Ernestine Gilbreth Carey (published in 1948)

Cry, the Beloved Country, by Alan Paton (published in 1948)

Death of a Salesman, by Arthur Miller (published in 1949)

What is your favorite book from the 1940s? Have you read I Capture the Castle? If so, did you love it as much as I did?! I’m also wondering if any of you have seen the movie inspired by the book; I noticed that it was rated R which surprised me since the book is so wholesome! It has me a bit nervous to check it out—I’m worried that it will massacre such a great story!